Lab 3 Spectral Indices & Transformations

Overview

The purpose of this lab is to enable you to extract, visualize, combine, and transform spectral data in GEE so as to highlight and indicate the relative abundance of particular features of interest from an image. At completion, you should be able to understand the difference between wavelengths, load visualizations displaying relevant indices, compare the relevant applications for varying spectral transformations, and compute and examine image texture.

3.1 Spectral Indices

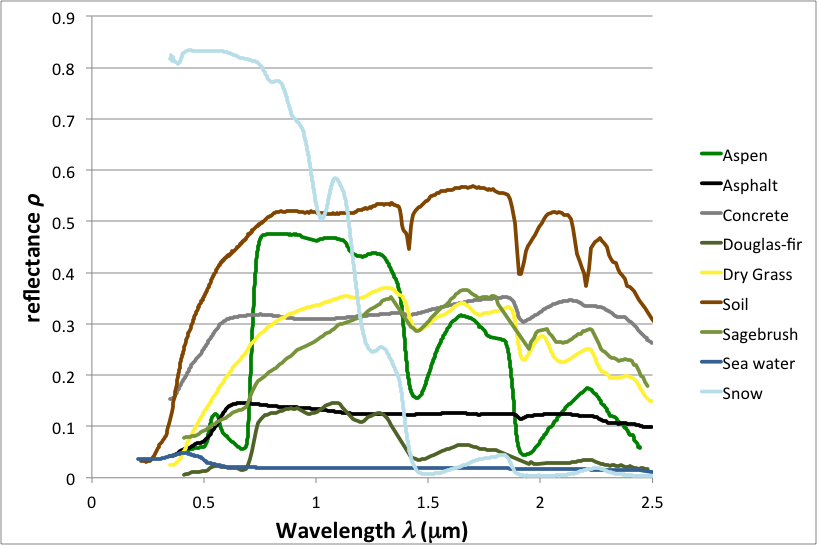

Spectral indices are based on the fact that reflectance spectra of different land cover types have unique characteristics. We can build custom indices designed to exploit these differences to accentuate particular land cover types. Consider the following chart of reflectance spectra for various targets.

Figure 3.1: Sample Spectral Reflectance Curves

Observe that the land covers are separable at one or more wavelengths. Note, in particular, that vegetation curves (green) have relatively high reflectance in the NIR range, where radiant energy is scattered by cell walls (Bowker et al. 1985). Also note that vegetation has low reflectance in the red range, where radiant energy is absorbed by chlorophyll. These observations motivate the formulation of vegetation indices, some of which are described in the following sections.

3.1.1 Important Indices

3.1.1.1 Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI)

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) has a long history in remote sensing. The typical formulation is

\[ \text{NDVI} = (\text{NIR} - \text{red}) / (\text{NIR} + \text{red}) \]

Where NIR and red refer to reflectance, radiance or DN at the respective wavelength. Implement indices of this form in Earth Engine with the normalizedDifference() method. First, get an image of interest by drawing a Point named point over SFO airport, importing the Landsat 8 Collection 1 Tier 1 TOA Reflectance as landsat8 and sorting the collection by cloud cover metadata:

var image = ee.Image(landsat8

.filterBounds(point)

.filterDate('2015-06-01', '2015-09-01')

.sort('CLOUD_COVER')

.first());

var trueColor = {bands: ['B4', 'B3', 'B2'],

min: 0, max: 0.3};

Map.addLayer(image, trueColor, 'image'); The NDVI computation is one line:

var ndvi = image.normalizedDifference(['B5', 'B4']); Display the NDVI image with a color palette (feel free to make a better one):

var vegPalette = ['white', 'green'];

Map.addLayer(ndvi, {min: -1, max: 1,

palette: vegPalette}, 'NDVI'); Use the Inspector to check pixel values in areas of vegetation and non-vegetation.

1. What are some of the sample pixel values of the NDVI in areas of vegetation vs. urban features vs. bare earth vs. water? Indicate which parts of the images you used and how you determined what each of their values were.

3.1.1.2 Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI)

The Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) is designed to minimize saturation and background effects in NDVI (Huete et al. 2002). Since it is not a normalized difference index, compute it with an expression:

var exp = '2.5 * ((NIR - RED) / (NIR + 6 * RED - 7.5 * BLUE + 1))';

var evi = image.expression( exp,

{'NIR': image.select('B5'),

'RED': image.select('B4'),

'BLUE': image.select('B2')

}); Observe that bands are referenced with the help of an object that is passed as the second argument to image.expression(). Display EVI:

Map.addLayer(evi,

{min: -1, max: 1, palette: vegPalette},

'EVI'); 2a. Compare EVI to NDVI across those same land use categories as in the previous question. What do you observe – how are the images and values similar or different across the two indices?

3.1.1.3 Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI)

The Normalized Difference Water Index (NDWI) was developed by Gao (1996) as an index of vegetation water content:

\[\text{NDWI} = (\text{NIR} - \text{SWIR})) / (\text{NIR} + \text{SWIR})\]

Compute NDWI in Earth Engine with:

var ndwi = image.normalizedDifference(['B5', 'B6']); And display:

var waterPalette = ['white', 'blue'];

Map.addLayer(ndwi,

{min: -0.5, max: 1,

palette: waterPalette},

'NDWI'); Note that this is not an exact implementation of NDWI, according to the OLI spectral response, since OLI does not have a band in the right position (1.26 𝛍m).

3.1.1.4 Normalized Difference Water Body Index (NDWBI)

It’s unfortunate that two different NDWI indices were independently invented in 1996. To distinguish, define the Normalized Difference Water Body Index (NDWBI) as the index described in McFeeters (1996):

\[\text{NDWBI} = (\text{green} - \text{NIR}) / (\text{green} + \text{NIR})\]

As previously, implement NDWBI with normalizedDifference() and display the result:

var ndwbi = image.normalizedDifference(['B3', 'B5']);

Map.addLayer(ndwbi,

{min: -1,

max: 0.5,

palette: waterPalette},

'NDWBI'); 2b. Compare NDWI and NDWBI. What do you observe?

3.1.1.5 Normalized Difference Bare Index (NDBI)

The Normalized Difference Bare Index (NDBI) was developed by Zha et al. (2003) to aid in the differentiation of urban areas:

\[ \text{NDBI} = (\text{SWIR} - \text{NIR}) / (\text{SWIR} + \text{NIR}) \]

Note that NDBI is the negative of NDWI. Compute NDBI and display with a suitable palette:

var ndbi = image.normalizedDifference(['B6', 'B5']);

var barePalette = waterPalette.slice().reverse();

Map.addLayer(ndbi, {min: -1, max: 0.5, palette: barePalette}, 'NDBI'); (Check this reference to demystify the palette reversal).

3.1.1.6 Burned Area Index (BAI)

The Burned Area Index (BAI) was developed by Chuvieco et al. (2002) to assist in the delineation of burn scars and assessment of burn severity. It is based on the spectral distance to charcoal reflectance. To examine burn indices, load an image from 2013 showing the Rim fire in the Sierra Nevadas:

var burnImage = ee.Image(landsat8

.filterBounds(ee.Geometry.Point(-120.083, 37.850))

.filterDate('2013-08-17', '2013-09-27')

.sort('CLOUD_COVER')

.first());Map.addLayer(burnImage, trueColor, 'burn image'); Closely examine the true color display of this image. Can you spot the fire? If not, the BAI may help. As with EVI, use an expression to compute BAI in Earth Engine:

var exp = '1.0 / ((0.1 - RED)**2 + (0.06 - NIR)**2)';

var bai = burnImage.expression( exp,

{'NIR': burnImage.select('B5'),

'RED': burnImage.select('B4')

}

); Display the result.

var burnPalette = ['green', 'blue', 'yellow', 'red'];

Map.addLayer(bai, {min: 0, max: 400, palette: burnPalette}, 'BAI');| 2c. Compare NDBI and the BAI displayed results – what do you observe? |

3.1.1.7 Normalized Burn Ratio Thermal (NBRT)

The Normalized Burn Ratio Thermal (NBRT) was developed based on the idea that burned land has low NIR reflectance (less vegetation), high SWIR reflectance (think ash), and high brightness temperature (Holden et al. 2005). Unlike the other indices, a lower NBRT means more burning. Implement the NBRT with an expression

var exp = '(NIR - 0.0001 * SWIR * Temp) / (NIR + 0.0001 * SWIR * Temp)'

var nbrt = burnImage.expression(exp,

{'NIR': burnImage.select('B5'),

'SWIR': burnImage.select('B7'),

'Temp': burnImage.select('B11')

}); To display this result, reverse the scale:

Map.addLayer(nbrt, {min: 1, max: 0.9, palette: burnPalette}, 'NBRT'); The difference in this index, before - after the fire, can be used as a diagnostic of burn severity (see van Wagtendonk et al. 2004).

3.1.1.8 Normalized Difference Snow Index (NDSI)

The Normalized Difference Snow Index (NDSI) was designed to estimate the amount of a pixel covered in snow (Riggs et al. 1994)

\[\text{NDSI} = (\text{green} - \text{SWIR}) /(\text{green} + \text{SWIR})\]

First, find a snow covered scene to test the index:

var snowImage = ee.Image(landsat8

.filterBounds(ee.Geometry.Point(-120.0421, 39.1002))

.filterDate('2013-11-01', '2014-05-01')

.sort('CLOUD_COVER')

.first());

Map.addLayer(snowImage, trueColor, 'snow image'); Compute and display NDSI in Earth Engine:

var ndsi = snowImage.normalizedDifference(['B3', 'B6']);

var snowPalette = ['red', 'green', 'blue', 'white'];

Map.addLayer(ndsi,

{min: -0.5, max: 0.5, palette: snowPalette},

'NDSI'); 3.1.2 Linear Transformations

Linear transforms are linear combinations of input pixel values. These can result from a variety of different strategies, but a common theme is that pixels are treated as arrays of band values.

3.1.2.1 Tasseled cap (TC)

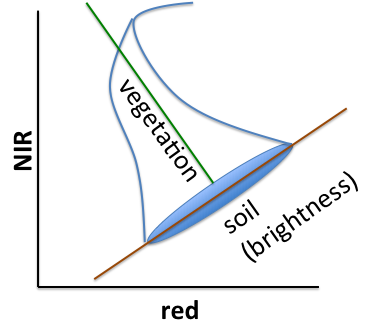

Based on observations of agricultural land covers in the NIR-red spectral space, Kauth and Thomas (1976) devised a rotational transform of the form

\[p_1 = R^T p_0 \]

where p_0 is the original px1 pixel vector (a stack of the p band values as an Array), p_1 is the rotated pixel and R is an orthonormal basis of the new space (therefore R^T is its inverse). Kauth and Thomas found R by defining the first axis of their transformed space to be parallel to the soil line in the following chart, then used the Gram-Schmidt process to find the other basis vectors.

Figure 3.2: Tassel Cap Illustration

Assuming that R is available, one way to implement this rotation in Earth Engine is with arrays. Specifically, make an array of TC coefficients:

var coefficients = ee.Array([

[0.3037, 0.2793, 0.4743, 0.5585, 0.5082, 0.1863],

[-0.2848, -0.2435, -0.5436, 0.7243, 0.0840, -0.1800],

[0.1509, 0.1973, 0.3279, 0.3406, -0.7112, -0.4572],

[-0.8242, 0.0849, 0.4392, -0.0580, 0.2012, -0.2768],

[-0.3280, 0.0549, 0.1075, 0.1855, -0.4357, 0.8085],

[0.1084, -0.9022, 0.4120, 0.0573, -0.0251, 0.0238]

]); Since these coefficients are for the TM sensor, get a less cloudy Landsat 5 scene. First, search for landsat 5 toa’, then import ‘USGS Landsat 5 TOA Reflectance (Orthorectified)’. Name the import landsat5, then filter and sort the collection as follows:

var tcImage = ee.Image(landsat5

.filterBounds(point)

.filterDate('2008-06-01', '2008-09-01')

.sort('CLOUD_COVER')

.first()); To do the matrix multiplication, first convert the input image from a multi-band image to an array image in which each pixel stores an array:

var bands = ['B1', 'B2', 'B3', 'B4', 'B5', 'B7'];

// Make an Array Image, with a 1-D Array per pixel.

var arrayImage1D = tcImage.select(bands).toArray();

// Make an Array Image with a 2-D Array per pixel, 6x1.

var arrayImage2D = arrayImage1D.toArray(1); Do the matrix multiplication, then convert back to a multi-band image:

var componentsImage = ee.Image(coefficients)

.matrixMultiply(arrayImage2D)

// Get rid of the extra dimensions.

.arrayProject([0])

// Get a multi-band image with TC-named bands.

.arrayFlatten(

[['brightness', 'greenness', 'wetness', 'fourth', 'fifth', 'sixth']]

); Finally, display the result:

var vizParams = {

bands: ['brightness', 'greenness', 'wetness'],

min: -0.1, max: [0.5, 0.1, 0.1]

};

Map.addLayer(componentsImage, vizParams, 'TC components'); 3a. Upload the resulting componentsImage and interpret your output.

3.1.2.2 Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

Like the TC transform, the PCA transform is a rotational transform in which the new basis is orthonormal, but the axes are determined from statistics of the input image, rather than empirical data. Specifically, the new basis is the eigenvectors of the image’s variance-covariance matrix. As a result, the PCs are uncorrelated. To demonstrate, use the Landsat 8 image, converted to an array image:

var bands = ['B2', 'B3', 'B4', 'B5', 'B6', 'B7', 'B10', 'B11'];

var arrayImage = image.select(bands).toArray(); In the next step, use the reduceRegion() method to compute statistics (band covariances) for the image. (Here the region is just the image footprint):

var covar = arrayImage.reduceRegion({

reducer: ee.Reducer.covariance(),

maxPixels: 1e9

});

var covarArray = ee.Array(covar.get('array')); A reducer is an object that tells Earth Engine what statistic to compute. Note that the result of the reduction is an object with one property, array, that stores the covariance matrix. The next step is to compute the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of that covariance matrix:

var eigens = covarArray.eigen(); Since the eigenvalues are appended to the eigenvectors, slice the two apart and discard the eigenvectors

var eigenVectors = eigens.slice(1, 1); Perform the matrix multiplication, as with the TC components:

var principalComponents = ee.Image(eigenVectors).matrixMultiply(arrayImage.toArray(1)); Finally, convert back to a multi-band image and display the first PC:

var pcImage = principalComponents

// Throw out an an unneeded dimension, [[]] -> [].

.arrayProject([0])

// Make the one band array image a multi-band image, [] -> image.

.arrayFlatten(

[['pc1', 'pc2', 'pc3', 'pc4', 'pc5', 'pc6', 'pc7', 'pc8']]

);

Map.addLayer(pcImage.select('pc1'), {}, 'PC'); Use the layer manager to stretch the result. What do you observe? Try displaying some of the other principal components.

3b. How much did you need to stretch the results to display outputs for principal component 1? Display and upload images of each the other principal components, stretching each band as needed for visual interpretation and indicating how you selected each stretch. How do you interpret each PC band? On what basis do you make that interpretation?

3.1.2.3 Spectral Unmixing

The linear spectral mixing model is based on the assumption that each pixel is a mixture of “pure” spectra. The pure spectra, called endmembers, are from land cover classes such as water, bare land, vegetation. The goal is to solve the following equation for f, the Px1 vector of endmember fractions in the pixel:

\[ Sf = p \]

where S is a BxP matrix in which the columns are P pure endmember spectra (known) and p is the Bx1 pixel vector when there are B bands (known). In this example, \(B= 6\):

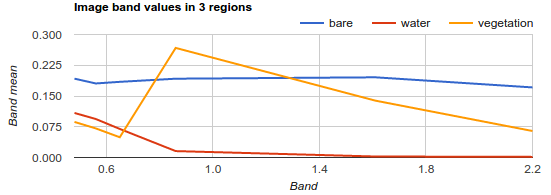

var unmixImage = image.select(['B2', 'B3', 'B4', 'B5', 'B6', 'B7']); The first step is to get the endmember spectra. Do that by computing the mean spectra in polygons delineated around regions of pure land cover. Zoom the map to a location with homogeneous areas of bare land, vegetation and water (hint: SFO). Visualize the input as a false color composite.

Map.addLayer(image, {bands: ['B5', 'B4', 'B3'], max: 0.4}, 'false color'); Using the geometry drawing tools, make three new layers (P=3) by clicking + new layer. In the first layer, digitize a polygon around pure bare land; in the second layer make a polygon of pure vegetation; in the third layer, make a water polygon. Name the imports bare, veg, and water, respectively. Check the polygons you made by charting mean spectra in them using Chart.image.regions():

print(Chart.image.regions(unmixImage, ee.FeatureCollection([

ee.Feature(bare, {label: 'bare'}),

ee.Feature(water, {label: 'water'}),

ee.Feature(veg, {label: 'vegetation'})]),

ee.Reducer.mean(), 30, 'label', [0.48, 0.56, 0.65, 0.86, 1.61, 2.2]));Your chart should look something like:

Figure 3.3: Spectral Chart

Use the reduceRegion() method to compute mean spectra in the polygons you made. Note that the return value of reduceRegion() is a Dictionary, with reducer output keyed by band name. Get the means as a List by calling values():

var bareMean = unmixImage.reduceRegion(

ee.Reducer.mean(), bare, 30).values();

var waterMean = unmixImage.reduceRegion(

ee.Reducer.mean(), water, 30).values();

var vegMean = unmixImage.reduceRegion(

ee.Reducer.mean(), veg, 30).values(); Each of these three lists represents a mean spectrum vector. Stack the vectors into a 6x3 Array of endmembers by concatenating them along the 1-axis (or columns direction):

var endmembers = ee.Array.cat([bareMean, vegMean, waterMean], 1); Turn the 6-band input image into an image in which each pixel is a 1D vector (toArray()), then into an image in which each pixel is a 6x1 matrix (toArray(1)):

var arrayImage = unmixImage.toArray().toArray(1);Now that the dimensions match, in each pixel, solve the equation for f:

var unmixed = ee.Image(endmembers).matrixSolve(arrayImage);Finally, convert the result from a 2D array image into a 1D array image (arrayProject()), then to a multi-band image (arrayFlatten()). The three bands correspond to the estimates of bare, vegetation and water fractions in f:

var unmixedImage = unmixed.arrayProject([0])

.arrayFlatten(

[['bare', 'veg', 'water']]

); Display the result where bare is red, vegetation is green, and water is blue (the addLayer() call expects bands in order, RGB)

Map.addLayer(unmixedImage, {}, 'Unmixed'); 3c. Upload the mean spectra chart you generated for bare, water, and land. Then upload the resulting map and interpret the output of the unmixedImage.

3.1.2.4 Hue-Saturation-Value Transform

The Hue-Saturation-Value (HSV) model is a color transform of the RGB color space. Among many other things, it is useful for pan-sharpening. This involves converting an RGB to HSV, swapping the panchromatic band for the value (V), then converting back to RGB. For example, using the Landsat 8 scene:

// Convert Landsat RGB bands to HSV

var hsv = image.select(['B4', 'B3', 'B2']).rgbToHsv();

// Convert back to RGB, swapping the image panchromatic band for the value.

var rgb = ee.Image.cat([

hsv.select('hue'),

hsv.select('saturation'),

image.select(['B8'])]).hsvToRgb();

Map.addLayer(rgb, {max: 0.4}, 'Pan-sharpened'); 3d. Compare the pan-sharpened image with the original image. What do you notice that’s different? The same?

3.2 Spectral Transformation

3.2.1 Linear Filtering

In the present context, linear filtering (or convolution) refers to a linear combination of pixel values in a neighborhood. The neighborhood is specified by a kernel, where the weights of the kernel determine the coefficients in the linear combination. (For this lab, the terms kernel and filter are interchangeable.) Filtering an image can be useful for extracting image information at different spatial frequencies. For this reason, smoothing filters are called low-pass filters (they let low-frequency data pass through) and edge detection filters are called high-pass filters. To implement filtering in Earth Engine use image.convolve() with an ee.Kernel for the argument.

3.2.1.1 Smoothing

Smoothing means to convolve an image with a smoothing kernel.

A simple smoothing filter is a square kernel with uniform weights that sum to one. Convolving with this kernel sets each pixel to the mean of its neighborhood. Print a square kernel with uniform weights (this is sometimes called a “pillbox” or “boxcar” filter):

// Print a uniform kernel to see its weights. print('A uniform kernel:', ee.Kernel.square(2));Expand the kernel object in the console to see the weights. This kernel is defined by how many pixels it covers (i.e.

radiusis in units of ‘pixels’). A kernel with radius defined in ‘meters’ adjusts its size in pixels, so you can’t visualize its weights, but it’s more flexible in terms of adapting to inputs of different scale. In the following, use kernels with radius defined in meters except to visualize the weights.Define a kernel with 2-meter radius (Which corresponds to how many pixels in the NAIP image? Hint: try projection.nominalScale()), convolve the image with the kernel and compare the input image with the smoothed image:

// Define a square, uniform kernel. var uniformKernel = ee.Kernel.square({ radius: 2, units: 'meters', }); // Filter the image by convolving with the smoothing filter. var smoothed = image.convolve(uniformKernel); Map.addLayer(smoothed, {bands: ['B4', 'B3', 'B2'], max: 0.35}, 'smoothed image');To make the image even smoother, try increasing the size of the neighborhood by increasing the pixel radius.

A Gaussian kernel can also be used for smoothing. Think of filtering with a Gaussian kernel as computing the weighted average in each pixel’s neighborhood. For example:

// Print a Gaussian kernel to see its weights. print('A Gaussian kernel:', ee.Kernel.gaussian(2)); // Define a square Gaussian kernel: var gaussianKernel = ee.Kernel.gaussian({ radius: 2, units: 'meters', }); // Filter the image by convolving with the Gaussian filter. var gaussian = image.convolve(gaussianKernel); Map.addLayer(gaussian, {bands: ['B4', 'B3', 'B2'], max: 0.25}, 'Gaussian smoothed image');

4a. What happens as you increase the pixel radius for each smoothing? What differences can you discern between the weights and the visualizations of the two smoothing kernels?

3.2.1.2 Edge Detection

Convolving with an edge-detection kernel is used to find rapid changes in DNs that usually signify edges of objects represented in the image data.

A classic edge detection kernel is the Laplacian kernel. Investigate the kernel weights and the image that results from convolving with the Laplacian:

// Define a Laplacian, or edge-detection kernel. var laplacian = ee.Kernel.laplacian8({ normalize: false }); // Apply the edge-detection kernel. var edgy = image.convolve(laplacian); Map.addLayer(edgy, {bands: ['B5', 'B4', 'B3'], max: 0.5, format: 'png'}, 'edges');

4b. Upload the image of edgy and describe the output

- Other edge detection kernels include the Sobel, Prewitt and Roberts kernels. Learn more about additional edge detection methods in Earth Engine.

3.2.1.3 Gradients

An image gradient refers to the change in pixel values over space (analogous to computing slope from a DEM).

- Use image.gradient() to compute the gradient in an image band.

// Load a Landsat 8 image and select the panchromatic band.

var Landsat8B8 = ee.Image('LANDSAT/LC08/C01/T1/LC08_044034_20140318').select('B8');

var xyGrad = Landsat8B8.gradient();

// Compute the magnitude of the gradient.

var gradient = xyGrad.select('x').pow(2)

.add(xyGrad.select('y').pow(2)).sqrt();

// Compute the direction of the gradient.

var direction = xyGrad.select('y').atan2(xyGrad.select('x'));- Gradients in the NIR band indicate transitions in vegetation. For an in-depth study of gradients in multi-spectral imagery, see Di Zenzo (1986).

–>

3.3 Additional Exercises

5a. Look in google scholar to identify 2-3 publications that have used NDVI and two-three that used EVI. For what purposes were these indices used and what was the justification provided for that index?

5b. Discuss a spectral index that we did not cover in this lab relates to your area of research/interest. What is the the name of the spectral index, the formula used to calculate it, and what is it used to detect? Provide a citation of an academic article that has fruitfully used that index.

5c. Find 1-2 articles that use any of the linear transformation methods we practiced in this lab in the service of addressing an important social issue (e.g., one related to agriculture, environment, or development). Provide the citations and discussed how the transformation is used and how it’s justified in the article.

Where to submit

Submit your responses to these questions on Gradescope by 10am on Wednesday, September 22. If needed, the access code for our course is 6PEW3W.