Lab 1 Remote Sensing Background

Overview

The purpose of this lab is to introduce digital images, datum, and projections, as well as demonstrate concepts of spatial, spectral, temporal and radiometric resolution. You will be introduced to image data from several sensors aboard various platforms. At the completion of the lab, you will be able to understand the difference between remotely sensed datasets based on sensor characteristics and how to choose an appropriate dataset based on these concepts.

Learning Outcomes

- Describe the following terms:

- Digital image

- Datum

- Projection

- Resolution (spatial, spectral, temporal, radiometric)

- Navigate the Google Earth Engine console to gather information about a digital image

- Evaluate the projection and attributes of a digital image

- Apply image visualization code in GEE to visualize a digital image

1.1 What is a digital image?

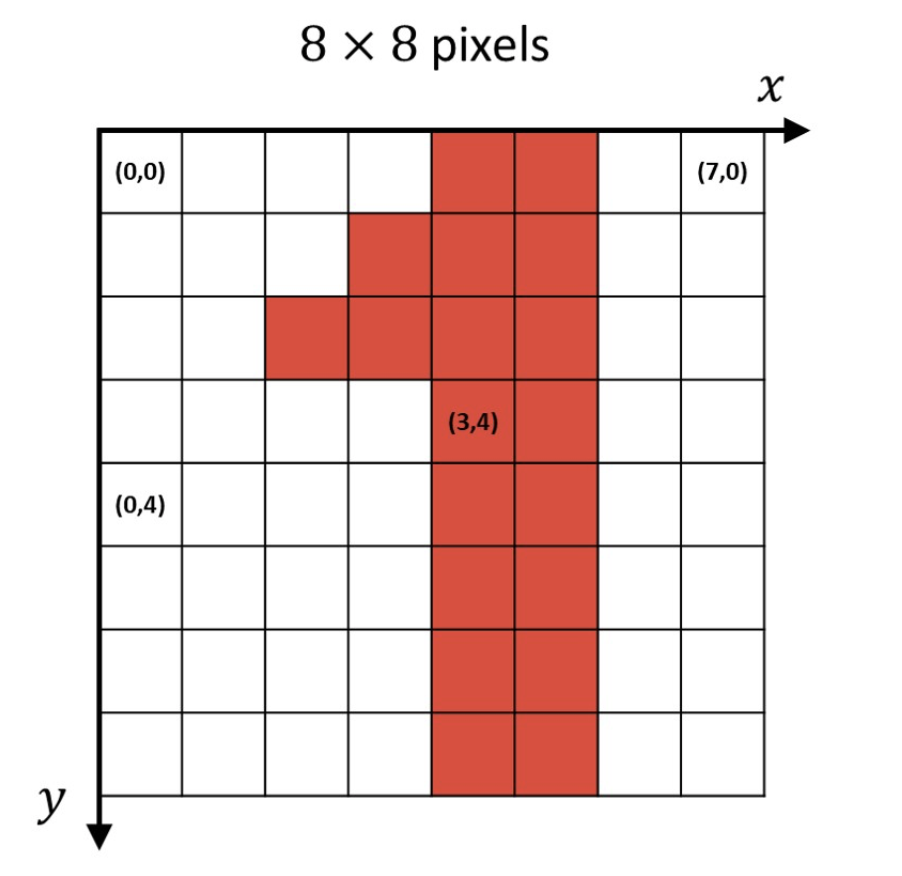

A digital image is a matrix of same-sized pixels that are each defined by two main attributes: (1) the position, as defined by rows and columns and (2) the a value associated with that position.

A digital image 8 pixels wide by 8 pixels tall could thus look like the image below. Note though you can reference the position from a given axis, typically, image processing uses the top-left of an image as the reference point, as in the below image.

Figure 1.1: Digital Image Example

A “traditional” optical photograph typically represents three layers (often the brightness values represented in the Red, Blue, and Green portions of the electromagnetic spectrum). Together, these three layers create a full-color photograph that is represented by a three dimensional matrix where pixel position is characterized by the (1) row (2) column (3) and layer.

Digital images are also often called rasters, and ESRI has a great overview of rasters used in geospatial analysis featured here.

1.1.1 From digital image to geospatial image

A digital image is a flat, square surface. However, the earth is round (spherical).

Thus to make use of the synoptic properties of remote sensing data, we need to align the pixels in our image to a real-world location. There’s quite a bit of mathematics involved in this process, but we will focus on two main components - establishing a Geographic Coordinate System (GCS) and a Projected Coordinate System (PCS).

The GCS defines the spherical location of the image whereas the PCS defines how the grid around that location is constructed. Because the earth is not a perfect sphere, there are different GCS for different regions, such as ‘North American Datum: 83’ which is used to accurately define North America, and ‘World Geodetic System of 1984’, which is used globally.

The PCS then constructs a flat grid around the GCS in which you can create a relationship between each pixel of a 2-dimensional image to the corresponding area on the world. Some of the common PCS formats include EPSG, Albers Conic, Lambert, Eckert, Equidistant, etc. Different types of PCS’s are designed for different formats, as the needs of a petroleum engineer working over a few square miles will differ from than a climate change researcher at the scope of the planet, for example.

ESRI (the makers of ArcGIS) has an article discussing the difference between GCS and PCS that provides further context. While you should be aware of the differences between GCS and PCS’s – especially when you intend to run analyses on the data you download from GEE in another system such as R, Python, or Arc – GEE takes care of much of the complexity of these differences behind the scenes. Further documentation on the GEE methodology can be found here. In our first exercise, we will show you how to identify the PCS so you can understand the underlying structure.

Furthermore, remote sensing data often consists of more than the three Red-Green-Bluye layers we’re used to seeing visualized in traditional photography. For instance, the Landsat 8 sensor has eleven bands capturing information from eleven different portions of the electromagentic spectrum, including near infrared (NIR) and thermal bands that are invisible to the human eye. Many Machine Learning projects also involve normalizing or transforming the information contained within each of these layers, which we will return to in subsequent labs.

In sum, understanding the bands available in your datasets, identifying which bands are necessary (and appropriate) for your analysis, and ensuring that these data represent consistent spatial locations is essential. While GEE simplifies many complex calculations behind the scenes, this lab will help us unpack the products available to us and their essential characteristics.

Summary

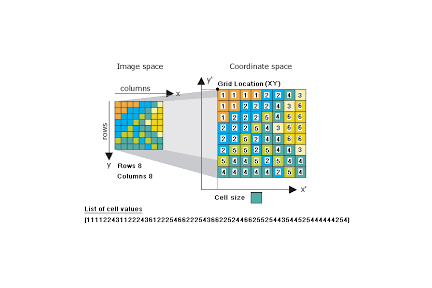

Each pixel has a position, measured with respect to the axes of some coordinate reference system (CRS), such as a geographic coordinate system. A CRS in Earth Engine is often referred to as a projection, since it combines a shape of the Earth with a datum and a transformation from that spherical shape to a flat map, called a projection.

Figure 1.2: A pixel, raster, and a CRS

1.1.2 Visualize a Digital Image

Let’s view a digital image in GEE to better understand this concept:

In the map window of GEE, click on the Point geometry tool using the geometry drawing tools to define your area of interest (for the purposes of consistency in this exercise, place a point on the Virginia Tech Drillfield, which will bring you roughly to

[-80.42,37.23]). As a reminder, you can find more information on geometry drawing tools in GEE’s Guides. Name the importpoint.Import NAIP imagery by searching for ‘naip’ and choosing the ‘NAIP: National Agriculture Imagery Program’ raster dataset. Name the import

naip.Get a single, recent NAIP image over your study area and inspect it:

// Get a single NAIP image over the area of interest. var image = ee.Image(naip .filterBounds(point) .sort('system:time_start', false) .first()); // Print the image to the console. print('Inspect the image object:', image); // Display the image with the default visualization. Map.centerObject(point, 18); Map.addLayer(image, {}, 'Original image');Expand the image object that is printed to the console by clicking on the dropdown triangles. Expand the property called

bandsand expand one of the bands (0, for example). Note that the CRS transform is stored in thecrs_transformproperty underneath the band dropdown and the CRS is stored in thecrsproperty, which references an EPSG code.EPSG Codes are 4-5 digit numbers that represent CRS definitions. The acronym EPGS, comes from the (now defunct) European Petroleum Survey Group. The CRS of this image is EPSG:26917. You can often learn more about those EPSG codes from thespatialreference.org or from the ESPG homepage.

The CRS transform is a list

[m00, m01, m02, m10, m11, m12]in the notation of this reference. The CRS transform defines how to map pixel coordinates to their associated spherical coordinate through an affine transformation. While affine transformations are beyond the scope of this class, more information can be found at Rasterio, which provides detailed documentation for the popular Python library designed for working with geospatial data.In addition to using the dropdowns, you can also access these data programmatically with the

.projection()method:// Display the projection of band 0 print('Inspect the projection of band 0:', image.select(0).projection());Note that the projection can differ by band, which is why it’s good practice to inspect the projection of individual image bands.

(If you call

.projection()on an image for which the projection differs by band, you’ll get an error.) Exchange the NAIP imagery with the Planet SkySat MultiSpectral image collection, and note that the error occurs because the ‘P’ band has a different pixel size than the others.Explore the

ee.Projectiondocs to learn about useful methods offered by theProjectionobject. To play with projections offline, try this tool.

1.1.3 Digital Image Visualization and Stretching

You’ve learned about how an image stores pixel data in each band as digital numbers (DNs) and how the pixels are organized spatially. When you add an image to the map, Earth Engine handles the spatial display for you by recognizing the projection and putting all the pixels in the right place. However, you must specify how to stretch the DNs to make an 8-bit display image (e.g., the min and max visualization parameters). Specifying min and max applies (where DN’ is the displayed value):

\[ DN' = \frac{ 255 (DN - min)}{(max - min)} \]

To apply a gamma correction (DN’ = DN\(_\gamma\)), use:

// Display gamma stretches of the input image. Map.addLayer(image.visualize({gamma: 0.5}), {}, 'gamma = 0.5'); Map.addLayer(image.visualize({gamma: 1.5}), {}, 'gamma = 1.5');Note that gamma is supplied as an argument to image.visualize() so that you can click on the map to see the difference in pixel values (try it!). It’s possible to specify

gamma,min, andmaxto achieve other unique visualizations.To apply a histogram equalization stretch, use the

sldStyle()method// Define a RasterSymbolizer element with '_enhance_' for a placeholder. var histogram_sld = '<RasterSymbolizer>' + '<ContrastEnhancement><Histogram/></ContrastEnhancement>' + '<ChannelSelection>' + '<RedChannel>' + '<SourceChannelName>R</SourceChannelName>' + '</RedChannel>' + '<GreenChannel>' + '<SourceChannelName>G</SourceChannelName>' + '</GreenChannel>' + '<BlueChannel>' + '<SourceChannelName>B</SourceChannelName>' + '</BlueChannel>' + '</ChannelSelection>' + '</RasterSymbolizer>'; // Display the image with a histogram equalization stretch. Map.addLayer(image.sldStyle(histogram_sld), {}, 'Equalized');The

sldStyle()method requires image statistics to be computed in a region (to determine the histogram).

1.2 Spatial Resolution

In the present context, spatial resolution often means pixel size. In practice, spatial resolution depends on the projection of the sensor’s instantaneous field of view (IFOV) on the ground and how a set of radiometric measurements are resampled into a regular grid. To see the difference in spatial resolution resulting from different sensors, let’s visualize data at different scales from different sensors.

1.2.1 MODIS

There are two Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectro-Radiometers (MODIS) aboard the Terra and Aqua satellites. Different MODIS bands produce data at different spatial resolutions. For the visible bands, the lowest common resolution is 500 meters (red and NIR are 250 meters). Data from the MODIS platforms are used to produce a large number of data sets having daily, weekly, 16-day, monthly, and annual data sets. Outside this lab, you can find a list of MODIS land products here.

Search for ‘MYD09GA’ and import ‘MYD09GA.006 Aqua Surface Reflectance Daily Global 1km and 500m’. Name the import

myd09.Zoom the map to San Francisco (SFO) airport:

// Define a region of interest as a point at SFO airport. var sfoPoint = ee.Geometry.Point(-122.3774, 37.6194); // Center the map at that point. Map.centerObject(sfoPoint, 16);To display a false-color MODIS image, select an image acquired by the Aqua MODIS sensor and display it for SFO:

// Get a surface reflectance image from the MODIS MYD09GA collection. var modisImage = ee.Image(myd09.filterDate('2017-07-01').first()); // Use these MODIS bands for red, green, blue, respectively. var modisBands = ['sur_refl_b01', 'sur_refl_b04', 'sur_refl_b03']; // Define visualization parameters for MODIS. var modisVis = {bands: modisBands, min: 0, max: 3000}; // Add the MODIS image to the map Map.addLayer(modisImage, modisVis, 'MODIS');Note the size of pixels with respect to objects on the ground. (It may help to turn on the satellite basemap to see high-resolution data for comparison.) Print the size of the pixels (in meters) with:

// Get the scale of the data from the first band's projection: var modisScale = modisImage.select('sur_refl_b01') .projection().nominalScale(); print('MODIS scale:', modisScale);Note these

MYD09data are surface reflectance scaled by 10000 (not TOA reflectance), meaning that clever NASA scientists have done a fancy atmospheric correction for you!

1.2.2 Multispectral Scanners

Multi-spectral scanners were flown aboard Landsats 1-5. (MSS) data have a spatial resolution of 60 meters.

Search for ‘landsat 5 mss’ and import the result called ‘USGS Landsat 5 MSS Collection 1 Tier 2 Raw Scenes’. Name the import

mss.To visualize MSS data over SFO (for a relatively cloud-free) image, use:

// Filter MSS imagery by location, date and cloudiness. var mssImage = ee.Image(mss .filterBounds(Map.getCenter()) .filterDate('2011-05-01', '2011-10-01') .sort('CLOUD_COVER') // Get the least cloudy image. .first()); // Display the MSS image as a color-IR composite. Map.addLayer(mssImage, {bands: ['B3', 'B2', 'B1'], min: 0, max: 200}, 'MSS');Check the scale (in meters) as before:

// Get the scale of the MSS data from its projection: var mssScale = mssImage.select('B1').projection().nominalScale(); print('MSS scale:', mssScale);

1.2.3 Thematic Mapper (TM)

The Thematic Mapper (TM) was flown aboard Landsats 4-5. (It was succeeded by the Enhanced Thematic Mapper (ETM+) aboard Landsat 7 and the Operational Land Imager (OLI) / Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS) sensors aboard Landsat 8.) TM data have a spatial resolution of 30 meters.

Search for ‘landsat 5 toa’ and import the first result (which should be ‘USGS Landsat 5 TM Collection 1 Tier 1 TOA Reflectance’. Name the import

tm.To visualize TM data over SFO, for approximately the same time as the MODIS image, use:

// Filter TM imagery by location, date and cloudiness. var tmImage = ee.Image(tm .filterBounds(Map.getCenter()) .filterDate('2011-05-01', '2011-10-01') .sort('CLOUD_COVER') .first()); // Display the TM image as a color-IR composite. Map.addLayer(tmImage, {bands: ['B4', 'B3', 'B2'], min: 0, max: 0.4}, 'TM');For some hints about why the TM data is not the same date as the MSS data, see this page.

Check the scale (in meters) as previously:

// Get the scale of the TM data from its projection: var tmScale = tmImage.select('B1').projection().nominalScale(); print('TM scale:', tmScale);

Question 1: By assigning the NIR, red, and green bands in RGB (4-3-2), what features appear bright red in a Landsat 5 image and why?

1.2.4 National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP)

The National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP) is an effort to acquire imagery over the continental US on a 3-year rotation using airborne sensors. The imagery has a spatial resolution of 1-2 meters.

Search for ‘naip’ and import the data set for ‘NAIP: National Agriculture Imagery Program’. Name the import naip. Since NAIP imagery is distributed as quarters of Digital Ortho Quads at irregular cadence, load everything from the closest year to the examples in its acquisition cycle (2012) over the study area and mosaic() it:

// Get NAIP images for the study period and region of interest. var naipImages = naip.filterDate('2012-01-01', '2012-12-31') .filterBounds(Map.getCenter()); // Mosaic adjacent images into a single image. var naipImage = naipImages.mosaic(); // Display the NAIP mosaic as a color-IR composite. Map.addLayer(naipImage, {bands: ['N', 'R', 'G']}, 'NAIP');Check the scale by getting the first image from the mosaic (a mosaic doesn’t know what its projection is, since the mosaicked images might all have different projections), getting its projection, and getting its scale (meters):

// Get the NAIP resolution from the first image in the mosaic. var naipScale = ee.Image(naipImages.first()). projection().nominalScale(); print('NAIP scale:', naipScale);

Question 2: What is the scale of the most recent round of NAIP imagery for the sample area (2018), and how did you determine the scale?

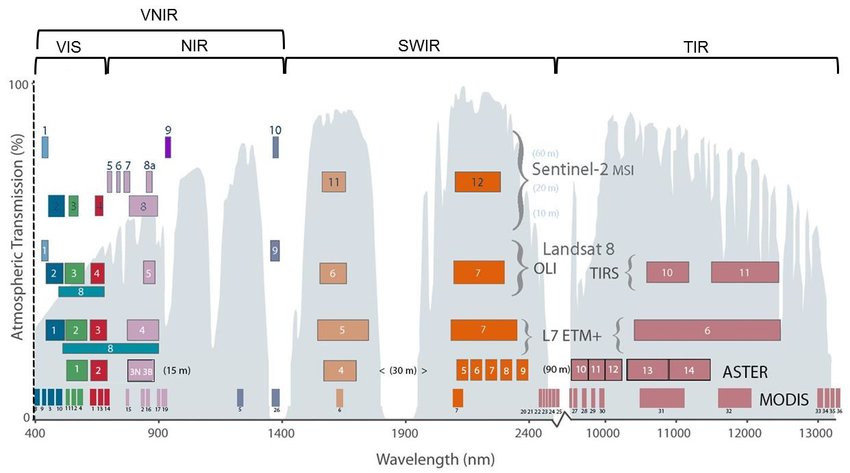

1.3 Spectral Resolution

Spectral resolution refers to the number and width of spectral bands in which the sensor takes measurements. You can think of the width of spectral bands as the wavelength intervals for each band. A sensor that measures radiance in multiple bands is called a multispectral sensor (generally 3-10 bands), while a sensor with many bands (possibly hundreds) is called a hyperspectral sensor (these are not hard and fast definitions). For example, compare the multi-spectral OLI aboard Landsat 8 to Hyperion, a hyperspectral sensor aboard the EO-1 satellite.

A figure representing common optical sensors and their spectral resolution can be viewed below (image source):

Figure 1.3: Common Optical Sensors and their Spectral Resolution

There is an easy way to check the number of bands in Earth Engine, but no way to get an understanding of the relative spectral response of the bands, where spectral response is a function measured in the laboratory to characterize the detector.

To see the number of bands in an image, use:

// Get the MODIS band names as a List var modisBands = modisImage.bandNames(); // Print the list. print('MODIS bands:', modisBands); // Print the length of the list. print('Length of the bands list:', modisBands.length());Note that only some of those bands contain radiometric data. Lots of them have other information, like quality control data. So the band listing isn’t necessarily an indicator of spectral resolution, but can inform your investigation of the spectral resolution of the dataset. Try printing the bands from some of the other sensors to get a sense of spectral resolution.

Question 3.1: What is the spectral resolution of the MODIS instrument, and how did you determine it?

Question 3.2: Investigate the bands available for the USDA NASS Cropland Data Layers (CDL). What does the band information for the CDL represent? Which band(s) would you select if you were interested in evaluating the extent of pasture areas in the US?

1.4 Temporal Resolution

Temporal resolution refers to the revisit time, or temporal cadence of a particular sensor’s image stream. Think of this as the frequency of pixels in a time series at a given location.

1.4.1 MODIS

MODIS (either Terra or Aqua) produces imagery at approximately a daily cadence. To see the time series of images at a location, you can print() the ImageCollection, filtered to your area and date range of interest. For example, to see the MODIS images in 2011:

// Filter the MODIS mosaics to one year.

var modisSeries = myd09.filterDate('2011-01-01', '2011-12-31');

// Print the filtered MODIS ImageCollection.

print('MODIS series:', modisSeries); Expand the features property of the printed ImageCollection to see a List of all the images in the collection. Observe that the date of each image is part of the filename. Note the daily cadence. Observe that each MODIS image is a global mosaic, so there’s no need to filter by location.

1.4.2 Landsat

Landsats (5 and later) produce imagery at 16-day cadence. TM and MSS are on the same satellite (Landsat 5), so it suffices to print the TM series to see the temporal resolution. Unlike MODIS, data from these sensors is produced on a scene basis, so to see a time series, it’s necessary to filter by location in addition to time:

// Filter to get a year's worth of TM scenes.

var tmSeries = tm

.filterBounds(Map.getCenter())

.filterDate('2011-01-01', '2011-12-31');

// Print the filtered TM ImageCollection.

print('TM series:', tmSeries);

Again expand the

featuresproperty of the printedImageCollection. Note that a careful parsing of the TM image IDs indicates the day of year (DOY) on which the image was collected. A slightly more cumbersome method involves expanding each Image in the list, expanding its properties and looking for the ‘DATE_ACQUIRED’ property.To make this into a nicer list of dates, map() a function over the ImageCollection. First define a function to get a Date from the metadata of each image, using the system properties:

var getDate = function(image) { // Note that you need to cast the argument var time = ee.Image(image).get('system:time_start'); // Return the time (in milliseconds since Jan 1, 1970) as a Date return ee.Date(time); };Turn the

ImageCollectioninto aListandmap() the function over it:var dates = tmSeries.toList(100).map(getDate);Print the result:

print(dates);

Question 4 What is the temporal resolution of the Sentinel-2 satellites? How can you determine this from within GEE?

1.5 Radiometric Resolution

Radiometric resolution refers to the ability of an imaging system to record many levels of brightness: coarse radiometric resolution would record a scene with only a few brightness levels, whereas fine radiometric resolution would record the same scene using many levels of brightness. Some also consider radiometric resolution to refer to the precision of the sensing, or the level of quantization.

Radiometric resolution is determined from the minimum radiance to which the detector is sensitive (Lmin), the maximum radiance at which the sensor saturates (Lmax), and the number of bits used to store the DNs (Q):

\[ \text{Radiometric resolution} = \frac{(L_{max} - L_{min})}{2^Q} \]

It might be possible to dig around in the metadata to find values for Lmin and Lmax, but computing radiometric resolution is generally not necessary unless you’re studying phenomena that are distinguished by very subtle changes in radiance.

1.6 Resampling and ReProjection

Earth Engine makes every effort to handle projection and scale so that you don’t have to. However, there are occasions where an understanding of projections is important to get the output you need. As an example, it’s time to demystify the reproject() calls in the previous examples. Earth Engine requests inputs to your computations in the projection and scale of the output. The map attached to the playground has a Maps Mercator projection.

The scale is determined from the map’s zoom level. When you add something to this map, Earth Engine secretly reprojects the input data to Mercator, resampling (with nearest neighbor) to screen resolution pixels based on the map’s zoom level, then does all the computations with the reprojected, resampled imagery. In the previous examples, the reproject() calls force the computations to be done at the resolution of the input pixels: 1 meter.

Re-run the edge detection code with and without the reprojection (Comment out all previous

Map.addLayer()calls except for the original one)// Zoom all the way in. Map.centerObject(point, 21); // Display edges computed on a reprojected image. Map.addLayer(image.convolve(laplacianKernel), {min: 0, max: 255}, 'Edges with little screen pixels'); // Display edges computed on the image at native resolution. Map.addLayer(edges, {min: 0, max: 255}, 'Edges with 1 meter pixels');What’s happening here is that the projection specified in

reproject()propagates backwards to the input, forcing all the computations to be performed in that projection. If you don’t specify, the computations are performed in the projection and scale of the map (Mercator) at screen resolution.You can control how Earth Engine resamples the input with

resample(). By default, all resampling is done with the nearest neighbor. To change that, callresample()on the inputs. Compare the input image, resampled to screen resolution with a bilinear and bicubic resampling:// Resample the image with bilinear instead of the nearest neighbor. var bilinearResampled = image.resample('bilinear'); Map.addLayer(bilinearResampled, {}, 'input image, bilinear resampling'); // Resample the image with bicubic instead of the nearest neighbor. var bicubicResampled = image.resample('bicubic'); Map.addLayer(bicubicResampled, {}, 'input image, bicubic resampling');Try zooming in and out, comparing to the input image resampled with the nearest with nearest neighbor (i.e. without

resample()called on it).You should rarely, if ever, have to use

reproject()andresample(). Do not usereproject()orresample()unless necessary. They are only used here for demonstration purposes.

1.7 Additional Exercises

Now that we have some familiarity with higher quality images, lets look at a few from the (broken) Landsat 7 satellite. Using your downloading skills, now select an image that contains the Blacksburg area with minimal cloud cover from Landsat 7 (for now, using the Collection 1 Tier 1 calibrated top-of-atmosphere (TOA) reflectance data product). Look at the image.

Question 5: What is the obvious (hint: post-2003) problem with the Landsat 7 image? What is the nature of that problem and what have some researchers done to try to correct it? (please research online in addition to using what you have learned in class/from the book) —

Question 6: Name three major changes you can view in the Blacksburg Area in the last decade using any of the above imagery (and state the source).

Conduct a search to compare the technical characteristics of the following sensors:

- MODIS (NASA) versus Sentinel (ESA), and

- AVHRR (NASA) versus IRS-P6 (or choose another Indian Remote Sensing satellite)

Question 7: Based on the characteristics you describe, for which applications is one sensor likely to be more suitable than the other ones?

Note: when using the internet to answer this question, be sure to cite your sources and ensure that you are obtaining information from an official, reputable source!

Where to submit

Submit your responses to these questions on Gradescope by 10am on Wednesday, September 8. All students who have been attending class have already been enrolled in Gradescope, although if for some reason you need to sign up again, the access code for our course is 6PEW3W.